What does it mean to ‘look the part’?

Dress and adornment is an essential part of human experience no matter what part of the world we live in, and clothing plays an important role in society. While cultures, aesthetics and climates mean that people’s dress can appear very different, we can deduce that the primary uses and purposes of clothing are very similar from one community to another: modesty, protection, identity, and creativity, for example. Clothes are used to cover bodies from nakedness and harsh climactic conditions, certain colours or accessories can indicate group affiliation or occupation and act as status markers, decoration can boost appearance and express uniqueness, and special dress can signify important life stages and ceremonies.

A Swahili proverb from East Africa says that ‘Character is not like clothing: it is not easily changed.’ Once, fashion was very local: today famous European and American designers influence fashion around the world. Jeans and t-shirts are everywhere, but many people dress to ‘look the part’ for work, for sport, for special occasions, for going out and sometimes for staying in at home. Both Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and Kitale Museum in Kenya have fashion collections focusing on women’s dress and accessories.

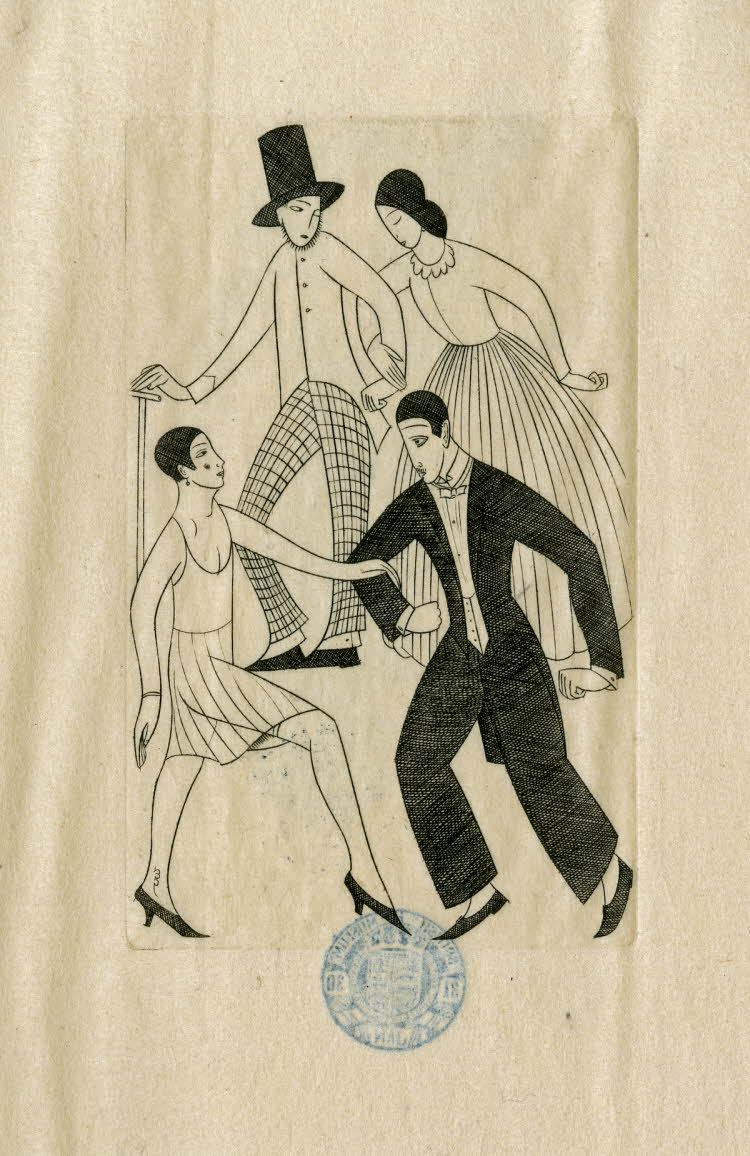

This Eric Gill engraving, and its title, might spark some ideas. It forms part of a collection by Gill that was published by the Bristol bookshop owner and radio producer Douglas Cleverdon. Cleverdon was associated with a number of leading cultural figures, and collaborated on various projects with Gill.

Collecting 1960s Bristol

The 1960s were a pivotal moment for social and personal identity in the UK. BMAG holds a collection of items relating to ‘Fun in the 1960s’, as well as a collection of 20th century dresses.

For many in Bristol and across the UK, the 1960s were a time of economic boom and greater social freedom. People had more time and money to spend on enjoying themselves. Families bought their first cars, televisions and washing machines. It was also a time of protest and social change, as demonstrated by the Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963, against racist employment policies by the local bus company.

The baby boom generation was coming of age, and the ‘teenager’ was invented. They didn’t want to dress like their parents. The Glen nightclub and the Locarno ballroom were popular spots. Coffee bars were the place to be, and several opened in the centre of Bristol, along with a Wimpy fast-food outlet on Union Street. Broadmead was full of exciting shops, particularly C&A on Penn Street – which offered affordable fashion for young people.

Many women made their own clothes from paper patterns, allowing them to follow the latest fashions. A lucky few owned the real thing, from designers like Mary Quant. Later in the 1960s, miniskirts, innovative fabrics and bold prints and psychedelic patterns made for striking clothes, matched with cheap and glittery fashion accessories.

The miniskirt was created by Mary Quant in 1965 and was widespread by 1967. The mini was worn by young women wanting to dress differently from their mothers, a trend which started in the 1950s. At four inches (10 cm) above the knee, old fogies condemned it as outrageous and immodest, while young women wore it because it was the fashion.

Fashion changed in other ways apart from style. Easy to wash synthetic fabrics became ever more popular, as few homes had washing machines and women had less time for housework as they increasingly went out to work. Colour and pattern followed the Swinging Sixties, and plain colour, black and white op-art and modern florals turned into the psychedelia of the hippy aesthetic.

A night out meant the latest fashion, whether shop-bought or home-made. The Mecca New Entertainments Leisure Centre, opened in the mid-sixties, the largest entertainment venue in Europe. At its heart was the Locarno ballroom. The opening night saw cocktails served by fully-dressed waiters in top hats, while ‘dolly birds’ in fish-net tights and grass skirts danced on the revolving stage, and Mecca hostesses in bikinis circulated amongst the guests – this was normal for the time. The Locarno would have seen a dizzying array of fashion pass through, from fans of The Who to those of The Clash.

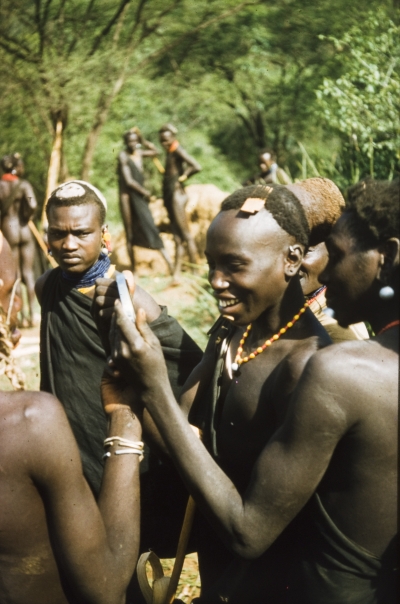

In the photograph below, from the archives of the Bristol Commonwealth and Empire collection, we see an encounter between British and Kenyan fashion-consciousness. A Suk (Pokot) porter, working with a British forestry survey team, looks at his reflection in the shaving mirror of Henry Osmaston (Working Plans Officer, Uganda Forest Department) on a safari to the Karasuk hills, Kenya. The photograph was taken in May 1959, on the cusp of a pivotal decade for the UK and for Kenya: the decade of decolonisation and counter-cultures.

© British Empire and Commonwealth Collection at Bristol Archives 2001/291/1/4/III/82 (Lang Brown Collection)

Pokot and Turkana Fashions

Kitale Museum owes its beginning to the collecting activities of amateur naturalist Lt Colonel Fredrick Stoneham, who lived in the Cherangany Hills, close to Kitale, until his death in 1966. In the early 1970s, his collections became the foundation of Kitale Museum, one of the first regional museums in Kenya. From this humble beginning, Kitale Museum has grown to be one of the most important education and tourist attractions in the country.

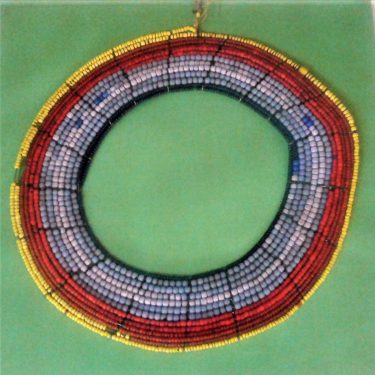

The museum’s first curator was Linda Donley-Reid, who had been a Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya, and later became the curator of Lamu Museum. During the early 1970s, time was spent on the acquisition of materials for the new museum’s exhibits, including a lot of ethnographic materials collected from surrounding ethnic groups. Donley-Reid personally collected these Pokot and Turkana women’s clothing objects from the communities during this time and donated them to the museum in 1988. Other clothing items in the collection come from the Luo, Luhya, Sabaot and Kalenjin (Nandi) communities. Kitale is a multi-ethnic town and the museum aims to represent each community’s culture through its collection.

“I have chosen to present Pokot and Turkana clothing items as these clothing traditions are alive today, especially during naming, circumcision and marriage ceremonies. The museum I work for, Kitale Museum, aims to represent the cultures of many local communities through collecting items. Although Kitale Museum does not own many Pokot and Turkana clothing items they contribute to the collections of local cultures which are an ideal learning resource for pupils, students and researchers.”

– Wendland Chole Kiziili

Dressing for Pokot and Turkana communities has been mainly concentrated on the girl child, recognised for her importance in society as well as her beauty. Dressing has traditionally identified those girls who are ready for marriage, and has been important for marriage negotiation between families.

Collecting Turkana and Pokot Fashions

As Bristol fashions have adapted, so have those of Kenyan communities: the introduction of new materials, such as plastic, as well as mass manufacture, have affected dress traditions in both the UK and Kenya.

The Kitale region of Kenya has had a lot of contact with agents of change; missionaries and colonial authorities brought with them Christianity and Western education. Missionaries considered Turkana and Pokot cultures and clothing to represent a primitive, less civilised way of life, and those who accepted to enter the missionaries’ churches and schools were given Western clothing. However, the challenging terrain of the region meant that many Turkana and Pokot were living out of reach, and so communities in some areas managed to retain to a greater extent their cultures and cultural dress and reject Western schooling, keeping, for example, an oral tradition rather than moving to a written culture. With time, the government used force to push for change in these communities and slowly but surely education, religion, but also Western development work have meant that Pokot and Turkana people have now mainly dropped their cultural dress, except for during special ceremonies.

Innovations in Turkana and Pokot clothing were already being made before the colonial period. Specific metals were obtained locally and worked by blacksmiths to create forms that gave weight to cloth, so that it could not be moved by the wind and to stop it from tearing easily. Beads of different colours, sizes and shapes were sold by Asian traders on the Swahili coast, being brought inland, and bought by Turkana and Pokot people at markets, for decoration purposes. The Pokot and Turkana items seen in the images above have shown great signs of change and adaptation. New materials and new uses have evolved in a number of ways, influenced by factors such as education and colonisation among others.

Next Theme →

[foogallery id=”2244″]