Having Fun in Bristol & Kano and Kaduna States, Nigeria

As with other traditions, leisure activities are adapted and appropriated across geographical borders, and take on new ownership and significance with each new generation. Whether in Northern Nigeria or Bristol, people seek out entertainment through games, the movies and the world’s favourite sport: football. As these entertainment traditions move with the times, we – as museum professionals – will need to turn our heads towards collecting this contemporary material for the future. It represents a powerful repository for memory and nostalgia, and for shared experience across cultures.

Cinema: Local and Global

The experience of cinema-going is both transnational and very localised. As Brian Larkin explains, in his research on cinemas in Northern Nigeria, cinemas are ‘peculiar kinds of social spaces marked by a duality of presence and absence, rootedness and transport.’ Cinema can ‘make people, ideas and commodities mobile’, and the architecture of the buildings themselves often appears similar across the world and across different cultures. However, cinema theatres are also ‘parochial, an intimate part of the urban topography’, and a space that creates an experience. Going to the cinema is often a social occasion, an emotional encounter and a sensory event.

Cinema is transglobal, but local cultural and social rules may affect who can and cannot go and watch films: even what films can and cannot be shown. In Bristol and in Northern Nigeria, the experience of going to the cinema could be very different.

Extracts from Brian Larkin, ‘The Materiality of Cinema Theatres in Northern Nigeria’ in Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, 2004, 2002, Ginsburg, F.D., Abu-Lughod, L. and Larkin, B. eds, Richmond: University of California Press

A Bristol Screen Story

The 1930s saw the proliferation of cinemas throughout the UK, and Bristol was among the cities to experience this. The UK’s Odeon chain opened its first cinemas in 1933 and by 1940, it had 255 venues across the country. When the Odeon in Union Street, Bristol, opened on 16 July 1938, Odeon founder Oscar Deutsch claimed it was ‘the finest cinema in the country’. In 1946, the Bristol cinema was the centre of much media attention when the cinema’s manager, Robert Parrington Jackson, was shot in his office during a screening of ‘The Light that Failed’. The 2000 movie spectators were unaware and the murderer was never found although a petty criminal admitted to the shooting on his deathbed many years later.

From the end of the Second World War onwards, cinema in the UK experienced a slow decline, as ticket prices rose and more people stayed at home to watch their own television, and later to watch films on video. By the late 1960s, many cinemas closed, and cinema annual admissions reached their low point in 1984. Then the ‘multiplex’ cinemas arrived on the outskirts of cities in the late ’80s. Traditional cinemas could not compete, and more closed or changed, adding to the decline of many city centres. Cinemas had to adapt or close: some went from vast, ornate one-screen ‘picture palaces’ to cheaply decorated, smaller two- or three-screen venues, or took on an entirely new life as snooker halls, concert venues, bingo halls, pubs, and even churches and mosques.

Bristol’s Union Street Odeon was no exception to the struggle. In 1967, it was given a £100,000 renovation, but only seven years later, it was forced to become a three-screen venue. In December 1983, the cinema was gutted and rebuilt at a cost of nearly £4 million, with the old, grand ground-floor foyer becoming a shop. The Odeon survived to see the audiences come back to the cinema for the social experience of watching a film with a crowd of people. At the other end of the scale, Bristol also boasts a microplex cinema, The Cube. It is a tiny, independent, one-screen venue, run as a co-operative, making its own cola and giving free entry to asylum seekers.

Cinemas of Northern Nigeria

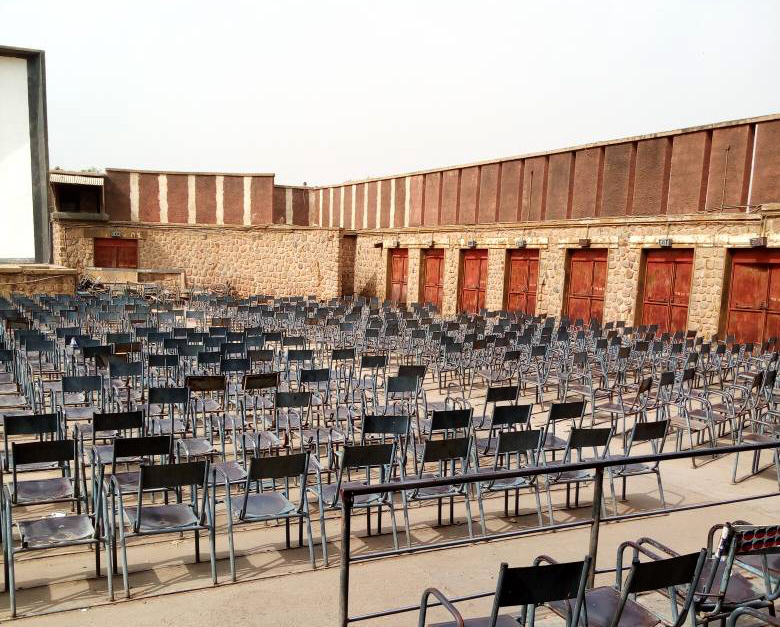

By 1934, movie-going had become a popular activity among Hausa youth in Northern Nigeria, who would attend screenings held at dance halls. In 1937, the city of Kano got its first purpose-built cinema, the Rex. Cinema was a controversial leisure activity in Hausa communities, with early Hausa names for the movies including majigi (magic) and dodon bango (evil spirits on the wall). When tragedy struck the El Duniya cinema in Kano in 1951, with a fire killing 331 of the cinema’s 600-person audience, there were rumours that the film had contained an image of the Prophet Muhammad and that this was divine punishment. Cinemas were mainly built outside of the Hausa Old City of Kano in more secular neighbourhoods such as Sabon Gari, populated by southern Nigerian Christian migrant workers. When the Palace cinema was built in the Old City in 1953, a fatwa was briefly issued to forbid the projection of films. There was violence upon the cinema’s opening, with the police arresting youths for stoning cinema-goers for several months after.

The cinema had a reputation as an illicit, immoral, un-Islamic location, but was nonetheless popular among the youth, somewhere social mixing was allowed between different groups. Cinemas were a British colonial introduction to the Northern Nigerian urban landscape, and a colonial transformation of social space. Cinema names in Kano often reflected empire ideology (Rex, Palace, Queen’s). The El Dorado cinema is one of Kano’s old cinemas and one of the few still standing. Its name betrays its colonial links, named after this concept associated with the imperialist imaginary – ‘the lost city of fabulous wealth waiting to be ‘discovered’.

While in the early post-independence period, young northern Nigerians flocked to cinemas in Kano, Kaduna, Jos and beyond, cinema culture began to wane by the 1970s. Economic crises and military coups effectively ended the distribution of Western films throughout most of Anglophone Africa. Though these were replaced with films from India and China, many urban Africans lost the cinema habit during the first decades of independence.

In the Northern Nigeria context, people point to many reasons behind the decline of the cinema – from the reputation of the audiences frequenting the venues, to the Westernisation of Bollywood, the introduction of Sharia Law, and the convenience of video. As in Bristol and the UK more widely, cinemas in northern Nigeria were converted to other uses, including churches and hospitals. Some were demolished, and others, including El Dorado, began to screen football matches in an attempt to draw in new audiences. As cinema-going declined, however, the filmmaking industry was booming in Nigeria, with video the most popular way of consuming the medium.

These days, Kano boasts the very contemporary Film House Cinema, with six digital screens, including two state-of-the-art 3D screens. However, the El Dorado remains important for many Northern Nigerians who grew up in the post-independence era. People still use its name as a mapping point in the city, even if they do not visit the cinema themselves – it is part of the structure of the city and is used for example, to tell a taxi driver which area of the city to drop you off in.

Extracts from Brian Larkin, ‘The Materiality of Cinema Theatres in Northern Nigeria’ in Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, 2004, 2002, Ginsburg, F.D., Abu-Lughod, L. and Larkin, B. eds, Richmond: University of California Press

Film Production in Bristol and Northern Nigeria

Many of us are familiar with the term Nollywood used to denote the Nigerian film industry. However, the Hausa-language film industry based in and around Kano is so popular that it has earned its own sobriquet, Kannywood.

Kannywood has been highly active since the beginning of the ’90s, in response to Hausa audiences’ love of Bollywood films, and it aims to merge Indian and Hausa culture cinematically. Nigeria is the second largest producer of films in the world, and Kannywood movies alone contribute around 60% of the total number of movies produced. As the Hausa language is spoken widely and used as a trade language in a number of countries beyond Nigeria – including Cameroon, Sudan, Ghana, Niger and Chad – Kannywood’s popularity extends beyond its locality. In 2017, the most popular Kannywood actor, Ali Nuhu, called for more cinemas in Kano State and other parts of northern Nigeria, to mirror the region’s filmmaking success.

Film Industry in Bristol

Bristol and Kano don’t just watch films, they also make films. Like Northern Nigeria, Bristol has a booming film industry. The city has been a major centre for TV and film production in the UK for many years. Bristol-based Aardman Animations gave us Creature Comforts, Wallace & Gromit, Chicken Run and more, and have won four Oscars.

The city of Bristol is home to BBC Bristol and the BBC Natural History Unit, which has created an industry nicknamed ‘Green Hollywood’ – the world’s largest concentration of firms producing wildlife content. Many movies and television series are filmed in the city, and it also houses the largest studios facility in the west of England, The Bottle Yard Studios – once a bottling plant for Bristol’s legendary Bristol Cream Sherry, and now home to eight film stages. The city celebrates its film industry by hosting eleven community-driven international film festivals each year, including Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival, Slapstick Festival and the WildScreen Festival of natural history films.

On 31 October 2017, Bristol was designated UNESCO City of Film – part of the UNESCO Global Creative Cities Network. This is a permanent status that celebrates Bristol’s achievements as a leading city in the field of film and moving image. The UNESCO status means that Bristol can focus on using film as a way to promote inclusivity, support cross-cultural initiatives, and reduce inequality and barriers.

Combining Movies and Football

Of the eleven cinemas that once existed in Kaduna State, between Kaduna and Zaria, more than half are now closed. The Scala and the Tudun Wala in Kaduna have been demolished and apartment buildings erected in their place. The Royal was converted into a church.

The Radar remains, however, and functions as both a cinema and a football ground, under the names of both Radar Cinema/Orange Theatre and San Siro Stadium (named after the home of AC Milan and Inter).

Football Spectatorship in Bristol and Kaduna

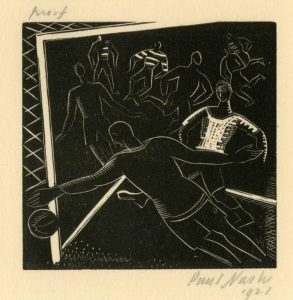

A love of sport can unite (or divide!) people across the world, and there is no sport more beloved in England and Nigeria than football. A scene of football playing or spectatorship is instantly recognisable and relatable, across time and cultures, whether this be a 1920s illustration for a book of character studies of Englishmen from the Cotswolds, near Bristol, or a contemporary photograph of amateur players in Kaduna, Northern Nigeria.

Like the cinemas in northern Nigeria, Bristol’s football grounds have experienced various lives. For example, Bristol Rovers’ ground at Eastville (shared with greyhound and speedway motorbike racing tracks) is now a shopping centre. The club moved to the Memorial Stadium, shared with the Bristol Rugby Football Club. This ground was built on an area first used for a ‘Buffalo Bill’ Wild West Show, then converted into allotments during the First World War. It opened officially as a sports ground in 1921, dedicated to the memory of local rugby union players who died in the War. Bristol has two football clubs, and one can’t mention one without the other. The City ground at Ashton Gate was built for the club, and hosts Championship games and big music events.

In Northern Nigeria, Kano Pillars Football Club is in the Nigerian Premier League. The club was founded in 1990, the year in which the professional association football league started in Nigeria. The Kaduna United Football Club plays at the Ahmadu Bello Stadium in Kaduna, which was designed in 1965 by famous modern English architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, who designed buildings in a number of former British colonies.

For amateur footballers in Bristol, the city has indoor, all-weather and outdoor football pitches that can be hired on a ‘pay to play’ basis or booked for regular games. Among Bristol’s amateur clubs, Ashton FC incorporates Ashton Boys (with around 340 players) and Ashton Girls (with around 65 players). The club was founded in 1994 and it is an established Charter Standard Community Club, which is the highest charter that can be achieved from the English Football Association. The Bristol Museum collection includes a number of items from the Ashton Boys’ football kit.

Scientific research has proved that food is strongly linked to nostalgia. The snacks we long for during a movie, a theatre interval, or half-time at a match may be different across cultures, but the feelings invoked are the same. Ice cream, hot dogs and popcorn are the traditional British cinema snacks: the bright orange drinks of the 1950s and ‘60s have been replaced by cola and coffee.

Gaming Traditions in Northern Nigeria

In Northern Nigeria, the game of wari is extremely popular. Wari is part of the mancala family of games, and different forms of this likely very ancient game are popular all over Africa. It is one of the world’s most successful games, having spread via migration routes across the world. It is as popular in parts of Asia and the Caribbean as it is in Africa. Wari has a strong social element: players encourage participation from onlookers, who discuss the game together and give their advice. The game is played fast and, as Sue has sadly learnt, even a seven-year-old child can beat an inexperienced player!

Colonial Connections

Bristol Archives holds the British Commonwealth and Empire Collection, a major collection of paper, photographic, film and sound archives that cover a broad range of subjects relating to the life of British Colonial Service staff and ‘subjects’ during this period. The Huxley Collection is one of those in the care of Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives. Elspeth Huxley CBE was a writer who lived in Kenya (then British East Africa) during her youth from 1913 to 1925, and returned to the continent periodically throughout her life. In her early life, she was an advocate for colonialism, but she later called for independence in African countries.

In this image, we can see a common sight in colonial archives: a British colonial settler playing an African board game (here mancala) with local people. The image of playing together, and of teaching and learning local traditions, conveys something of the complexity of the colonial relationship. The Kikuyu men are probably laughing because she is so slow at playing: they would play fast, continually calculating in their heads which pieces to move and which ones their opponent might move, whilst she would have to think about each move.

Gaming in the 21st Century

While games like wari continue to hold popularity, the advent of electronic games has taken hold worldwide. Mobile phones are prevalent across Northern Nigeria, as they are in the UK.

Museums in the UK have been collecting games from board games such as mancala, to early electronic games from the 1920s, to the most up-to-date computer games.

New games have been developed to tackle global changes from currency unions to electronic banking. Museums are keeping an eye on these trends, and collecting these important social documents for the future.

Next Theme →

[foogallery id=”2249″]