Sounds of the City

Often a place is remembered by what appealed to an individual’s senses. Memories are stirred because a familiar sound or feeling takes you back to a time and place. For Sue and Jana, identities of their homes were shaped by the sounds of their cities; in both cases this meant the centuries old and daily occurrence of public calls to worship. It also means the music for which their part of the world is known, and is present in their daily life through what they hear on the street, in local amenities and at cultural events and celebrations.

The Tolling of Bells and a Call to Prayer

Religious buildings continue to shape the landscapes of Christian and Muslim countries. Towering spires and Minerats either dominate the sky lines or compete with new sky scrapers. Not only do these buildings continue to draw attention architecturally but through the sounds of tolling of bells and proclamations of faith which call worshippers to their doors.

Manger Square, Bethlehem, photograph by Jana Alaraj, 2016

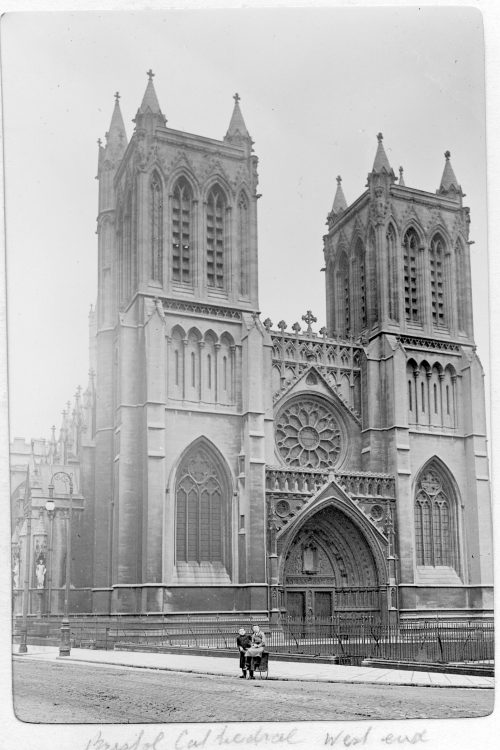

The Church Bells of Bristol

Bristol is a city of churches: a 1673 image shows 19 churches. Many closed in the late 20th century, but some have reopened to new Christian congregations over the past 20 years. The City of Bristol sits within the Diocese of Bristol, and is therefore under the pastoral care of the Archbishop of Canterbury. The diocese stretches from south Gloucestershire to north Wiltshire to Swindon, but the historic centre of the diocese is in Bristol, in the Bristol Cathedral. Today’s Cathedral began as an Augustinian Abbey in 1140, founded by a prominent local man Robert Fitzharding. The church transepts, chapter house and abbey gatehouse that stand today, date back to those origins. The rebuilding work of the 1530s was never finished due to Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries between 1536 – 1541. The Church itself might have been sold but it became one of Henry’s ‘new foundation Cathedrals’ – some suggest because of the campaigning efforts of the citizens of the second trading port to keep it as the local place of worship. For centuries the bells of Bristol Cathedral have been heard across the city as a central part of Christian workshop, calling people to the building for services, celebrations and during a crisis. The Cathedral has two sets of bells, one set is run electronically and another by hand, rung by volunteers and visiting groups. Today the bells chime every quarter hour to mark the time, toll for 10 minutes before daily services of Matin, Mass and Evensong, and for 30 minutes before Sunday Eucharist. The bells also ring for weddings and funerals, for special services and Friday evenings, when the bellringers hold their practice. They fell silent for the duration of World War Two until victory was declared, and more recently for repairs in 2017. Otherwise, they and the other church bells continue to ring out and summon the faithful to prayer.

The Citty of Bristoll map, U20 © Bristol Culture

The Bethlehem Azaan in Palestine

Religious buildings continue to shape the landscapes of Christian and Muslim countries. Towering spires and Minerats either dominate the sky lines or compete with new sky scrapers. Not only do these buildings continue to draw attention architecturally but through the sounds of tolling of bells and proclamations of faith which call worshippers to their doors.

The city of Bethlehem in Palestine has for centuries embraced people from all over the world who come as visitors, pilgrims or seekers of knowledge. The city combines Christian and Muslim culture in a harmonic way; one can hear chants coming from mosques minarets, blended with the chimes of the various churches in a mosaic of superb sounds. Two particular buildings, a church and a mosque, at the heart of the old city of Bethlehem, stand out framing the main square: Manger square. The Church of Nativity, which dates back to 6th century and is known as Christ’s birthplace, marks a stepping stone in the pilgrims’ route. The Mosque of Omar, built in 1860 AD, was named after the second Rashidun Muslim Caliph, Omar Ibn al-Khattab (581-644 AD). Historical accounts report that the two structures stand side by side because of the actions of Omar. Omar travelled to Bethlehem in 637 AD after the Siege of Jerusalem. Upon reaching the old city of Bethlehem, Omar declared his support and respect for the shrine and guaranteed security for all Christians and the clergy thus, the Church of Nativity was not transformed into a mosque at that time.

![]()

Today the juxtaposing architectural buildings are two of the oldest and foremost buildings in Bethlehem city that continue to be used for their original purpose. They manifest a Christian- Muslim coexistence and brotherhood and define the city’s spaces through sounds blended together creating a vibrant meeting point for locals and for the town’s pilgrims. The sounds shape a collective memory at the heart of the city through the various cultural activities that take place in Manger Square around the year. In the streets of Bethlehem the Azan / call can be heard 5 times a day every day.

Bethlehem Azaan sounds clip, recorded by Nabil Alaraj at the city center of Bethlehem.

‘Popular’ Music

Sue and Jana also expressed the importance of music to their cities. ‘Bristol Sound’ is a musical movement which Bristolians are particularly proud of as it has and continues to promote unique creativity and brings an international stage to its performers. For Palestinians across the world traditional Palestinian music is valued and constantly revived as it asserts a sense of belonging and identity, and stirs a sense of nostalgia.

Bristol Sound Music Scene

The city of Bristol is the biggest in the South West of England, one of the most racially diverse in the UK and renowned as a bustling centre of culture – as well as one of the best places to live in Britain.

Since the 1980s Bristol has become a recognised music scene through what is today known as the Bristol Sound. In the bars, clubs and pubs of Bristol, music genres such as drum & bass, dubstep, and many newer forms of bass music developed and trip-hop was born. The Bristol Sound is identified as having a sparseness and darkness because of the prominent baseline and melancholic lyrics. It has been suggested that the darkness within the music comes from the citizen’s conflict with their city’s history; through the slave trade and tobacco industry an aesthetically beautiful Georgian city was formed.

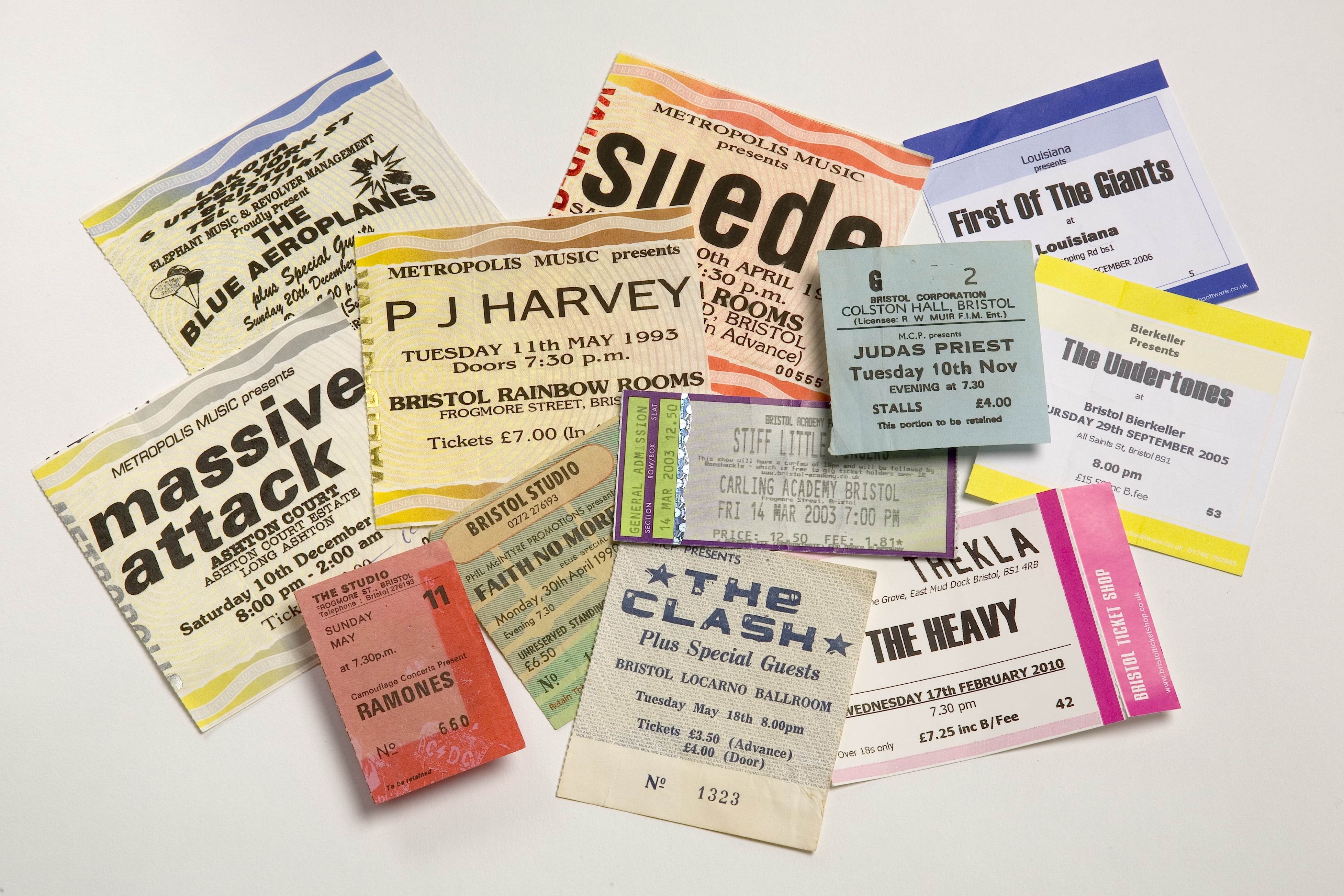

Today the city is buzzing with independent music venues hosting festivals and club nights, characterised by the Bristol Sound of the last three decades. Brisitol’s M Shed curated a temporary exhibition, Bristol Music: Seven decades of sound, to tell the stories of people in Bristol both making and listening to music and celebrate music in Bristol. It also asked what was special about the Bristol music scene…

Is there one definitive Bristol Sound?

Are the best days of Bristol music behind us?

Where in the city is the heart of musical Bristol?

Bristol Music: Seven Decades of Sound

Music Landscape Scene in Palestine, 20th and 21st Century

![]()

Palestine shares basic elements of musical traditions with Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, countries which are a part of the extended region of Palestine’s geographical location. In the 20th century Palestine and the region witnessed historical changes in many aspects including political, cultural and social thus affecting and transforming music production and style.

In the first half of the 20th century four genres of music prevailed: folkloric, Arabic classical, national anthems, and Western classical, all of which have been an integral part of Palestinian society, culture, and identity. The most prevalent music at that time was folkloric music: song accompanied by a rhythm. Lyrics were sung to the accompaniment of string instruments such as the rababa, shabbabah, yarghul, mijwiz, buzuq, tabla, daf and ‘ūd. It was spontaneous and unsophisticated, vibrant and alive and was used to express the general spirit of a people, therefore the lyrics that accompanied the music changed based on the emerging situation, for example, love, sorrow, grief. In the 20th century, coffeehouses (cafés), social celebrations in particular weddings, and small scale performances played a vital role in transmitting music from one generation to the next. Ya Zareef Al-tool (which you can listen to below) and Daloo’na are examples of the most famous types of Palestinian folkloric music. In the sound clip below the singing of Ya Zareef Al-tool is accompanied by the traditional ‘ūd instrument.

Ya Zareef Al-tool performed and recorded by musician Mufied Nihmeh

In 1936 the opening of the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS), by the British Mandate via the radio station in Jerusalem, offered many musicians the opportunity to perform and be heard on a national level. During this time (before 1948) Augustine Lama (1902–1988), Salvador Arnita (1914–1989), and Yousef Khasho (1927–96) were performing at the height of their careers and are now recognised as pioneers and major players in propagating classical music.

After the 1948 Nakba (when more than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes) many Palestinians found refuge in neighbouring countries and the music landscape scene came to a standstill. The scene changed drastically after 1967 when Israel occupied the rest of Palestine; musicians wrote music influenced by the Palestinian struggle and one of the most famous bands at that time was Al Ashiqeen founded in Damascus in 1977. They were famous for their national songs that were based on popular folkloric music.

Later in the 1990s, a new form of interest in music developed leading to the establishment of musical conservatories like The Edward Said National Conservatory of Music (1993) and the Al Kamandjâti Association (2002). Today these musical conservatories play an integral role in preserving traditions, identity and cultural values of the Palestinian society and open new musical scenes for Palestinians living across the globe.

Next Theme →

[foogallery id=”2251″]